Vargas' Podcasts

Powered by 🌱Roam GardenBeware of Refactor Purgatory

- Blog Post Complete

- Notes:

- Reference my previous experiences with Warshop and Cetacea - Refactoring hell

- Feedback

- Content {{word-count}}

- Before my friend over at Tuesday Labs, LLC created Longwave, there was an earlier iteration of this project called Cetacea. The premise of both projects were the same: a journal sharing app where every morning you get an email with your friends' journals. Cetacea was a project my girlfriend at the time and I worked on during my Master's year at MIT. We were able to get an MVP out to two journaling groups within the first semester. There was a large initial volume of journals and we often discussed them with the groups over dinner.

- As we explored new features we wanted to add, we realized a bunch of poor design choices we made at the start. Once we started working full time and saw how experienced teams architected fully featured systems, we realized even more how bad our initial decisions were. Learning all these lessons was inspiring. It made me eager to get back home to reimplement parts of Cetacea to match what I was learning at work.

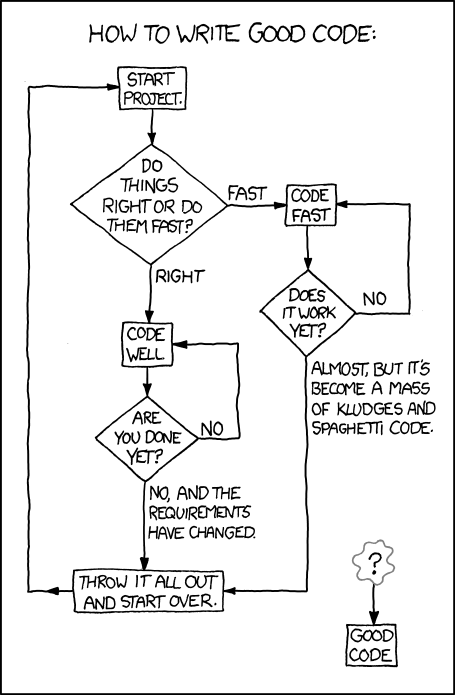

- First, we needed to rewrite the whole backend to make it more unit testable. Then we planned to rewrite the front end from scratch so that all pages could use the same layout and authentication system. Then we should rewrite the whole backend again to make adding new routes as easy as possible. On and on, new ideas on how to spin on the same hamster wheel kept me busy, all the while delaying actual features that users could benefit from. The lack of visible progress became deflating over time, work on the side project kept being deprioritized for other areas of life that saw visible progress, and eventually cetacea was abandoned.

- It's easy as a developer to get stuck in what I call "Refactor Purgatory". The allure of building some sweet abstraction that could save future you hours of tech debt is tempting enough to dive in and ignore work that could demonstrate visible progress. However, this constant focus for building for the future takes its toll. Not only will refactor-related roadblocks discourage you from actually continuing the project, several abstractions that you do end up building will become stale over time.

- Instead of over optimizing for the future, we should lean more towards the present.

- Do Things That Don't Scale

- There's a common mistake young engineers make with abstractions and as a young engineer, I was no different. We discover the DRY acronym and start commenting on every code review "Don't repeat yourself!". We do everything in our power to rip any character of code into a common function, while also making all sorts of ridiculous predictions of when we might repeat ourselves.

- My senior year, I started working on a game called Warshop. The first iteration of the game included cards, boards, special effects, and multiple players. Naive Vargas went to build abstractions for each and every one of these objects so that it would "be easy to add the next one". Except each next card always introduced a new mechanic that every previous one had to be redesigned to accommodate. And every new special effect needed a new property that every older one needed to demonstrate. All to finally realize upon play testing with actual users that our game would have neither cards or special effects in future iterations.

- In a response to DRY programming, Kent C. Dodd's wrote about AHA which he coined as Avoiding Hasty Abstractions. We often have very poor foresight on how what we're building will evolve over time. Or, as is the case with many smaller projects, if they will ever evolve at all. We should liberally copy and paste more in the early stages of our projects. While seemingly tedious in the short term, it will allow us to adapt to feedback in the long term.

- AHA programming is the engineering version of a more general idea gaining momentum with small business owners which is to do things that don't scale. Respond to every customer request. Use no code solutions for workflows. Try multiple ideas before deciding on one. Whether it's the beginning of a small college side project or the early days of a Silicon Valley startup, the rate of change will be too high to know what workflows are common enough to start abstracting away into automated code. Start too early or with not enough foresight, and you'll be stuck maintaining software that won't be used on the way to refactor purgatory.

- The key to motivating yourself past refactor purgatory is two-fold. The first is building something that shows off visible progress to someone else. The second is to keep finding the smallest possible task that incrementally makes progress.

- Visible Progress

- Visible progress is a great motivator because it allows other opinions to dictate what’s important to implement over just our own. When we are the only end user of what we're building, we get caught in just these developer quality of life refactors that don't provide anyone else any value. Because we are the only end user, we then weigh the cost of the refactor against the perceived value to ourselves. Inevitably, we conclude "meh, I don't need to do this". The project then heads to the graveyard.

- With external users, they have the final say on how much they value a feature. This encourages us to satisfy their ask by understanding what's the minimal viable version of what they want. The goal is never to have perfectly abstracted code, but to bring value to our end users. We are far more motivated to push the project forward when we see the effects of what we build on others.

- Incremental Progress

- Part of what gets you as a developer stuck in a refactor is the daunting size of the task. The prospect of having to change every function and every use case of a given abstraction is enough to let the project collect cobwebs for weeks. Simple find + replace is usually not enough. Sometimes we also want to change how a given class or function behaves internally across a bunch of different use cases. This often involves rewriting logic in several places and tests, beyond the capabilities of find + replace.

- Instead of being faced with a large task, focus on what could get done in short bursts of time. This helps limit the scopes of our changes. It forces us to ask, "what's the one thing I could do today to move this project forward?" It's a mentality that inherently begs us to be more present with our decision making and not feel so overburdened by the weight of a full code base refactor.

- Refactor Well

- This is not to say we should never refactor. There are times where technical debt accrues to the point where significant performance problems could visibly deteriorate the user's experience. Rather, before embarking on any refactor, one should keep both of the properties in the previous sections at the forefront of how to approach it.

- Refactors are intimidating. Because of this, force yourself to break it down to as many small pieces as possible. It's tempting to say "we won't know what it will take until we start rewriting functionality." This temptation was often a lazy excuse I used to avoid thinking through what I was rebuilding. Doing the work up front to break down what needs to be replaced will save hours of work trying to haphazardly do the same thing down the road.

- Make sure your refactors have visible improvements to others. Otherwise, what's the point? Satisfying our own developer quality of life often runs out of steam quickly. Benchmark each of the incremental pieces we broke down in the previous step with visible feature improvements that are now easier to implement. It's what will motivate you to push through the finish line.

- Refactors are often tempting, but could send you on a tailspin towards the end of the project. Strive to be more present, only embarking on redesigns when they could provide incremental, noticeable improvements to your end users.